Timelessness and relevance are the two determining factors of what I believe to be classic. Shakespeare’s universal hymns of the human condition keep his plays stacked in classroom shelves, and the Rolex Submariner will ever bequeath from wrist to wrist for generations – or as my father said when I asked if I can size his down to fit my wrist, “You’ll have to wait until I’m dead.” When it comes my time to pass it on, I can’t wait to see it on my child’s wrist, the patina of a dial decades under the sun, belonging in a generation for which it was made to last.

The classic aesthetic is something I look forward to in all arts, most particularly film. It’s fascinating to rewatch movies and see how they all age at different rates. The neon tanks and acid wash of most films from my birth decade will always identify as eighties movies, yet others will age much more gracefully, if not at all. I refer to the set wardrobe of movies because they place such a large influence in the aging of the film, which is why a 1997 film like Gattaca looks simultaneously like a 1957 film and 2017 film.

Even by today’s standards, Gattaca serves as a contemporary to the dangers of man playing the hand of God. It implicates the slippery slope of genetic discrimination, which is an increasingly real possibility. One reason why Andrew Niccol’s film resounds seventeen years after its release is by a taking a deliberately classic approach to style, which effectively serves to prevent distraction. In the “not-too-distant future” setting of the film, the plot remains the focus, rather than the filmmaker’s playhouse visions of floating cars and next-next level technology that usually misses the mark. I’m looking at you, 2015. The collective sigh of disappointment of a world without hover boards and the Champion Cubs is something that keeps me up at night.

Still, check out that suit. While there’s not much outside of sober blacks and grays in each character’s wardrobe, this only proves how easy it is to dress well. Don’t fuss with the flair; just make sure your suit fits, your hair matches and you’ll be fine. That’s exactly the hand our protagonist Vincent Freeman, aka “Jerome” must play to fulfill his pipe dream to space.

Still, check out that suit. While there’s not much outside of sober blacks and grays in each character’s wardrobe, this only proves how easy it is to dress well. Don’t fuss with the flair; just make sure your suit fits, your hair matches and you’ll be fine. That’s exactly the hand our protagonist Vincent Freeman, aka “Jerome” must play to fulfill his pipe dream to space.

To overcome gulf between the genetically elite and In-Valid, Ethan Hawke’s Vincent must commit to a daily ritual hours before blood-sampling into his shift at Gattaca. After scraping and burning off all remnants of his DNA, he must become the genetic code named Jerome by flocking in the same sartorial feather as colleagues, which he does with a boatload of double-breasted suits.

I’ll admit, the film’s style never detracts from its plot, but I sometimes rewatch certain scenes to appreciate his and his coworkers’ suits alone. Just look at that queue: the amount of shirt sleeve peeking from every single jacket sleeve is perfect – what you’d expect from an astronaut. Now, it’s never stated, but I think everyone silently agrees to commit to the same suiting cues to prove loyalty to Gore Vidal, who, as Director Josef, shows that even as an uppity curmudgeon, age and style mustn’t always drift in opposite directions.

I’ll admit, the film’s style never detracts from its plot, but I sometimes rewatch certain scenes to appreciate his and his coworkers’ suits alone. Just look at that queue: the amount of shirt sleeve peeking from every single jacket sleeve is perfect – what you’d expect from an astronaut. Now, it’s never stated, but I think everyone silently agrees to commit to the same suiting cues to prove loyalty to Gore Vidal, who, as Director Josef, shows that even as an uppity curmudgeon, age and style mustn’t always drift in opposite directions.

While most of the film’s style sticks to this dark, simple uniform sans a single pocket square, there are opportunities those fit with more adventure. Vincent likes to paint the town wine red in French cuffs and pearl links, but it’s in his genetic lender, Jerome aka “Eugene,” who wears risk with reward.

While most of the film’s style sticks to this dark, simple uniform sans a single pocket square, there are opportunities those fit with more adventure. Vincent likes to paint the town wine red in French cuffs and pearl links, but it’s in his genetic lender, Jerome aka “Eugene,” who wears risk with reward. The burgundy waistcoat is the only splash of real color in the film, and it’s no surprise only “Eugene” can indulge in it. What I love most is his hastily pulled tie; it can be taken as the work of a sloppy drunk, but for someone who is otherwise sharply dressed, it only personifies Eugene’s reckless abandon, which is the makings of true style; while Vincent hides in the guise of Jerome’s “just-like-everyone else” outfit of sober precision, Eugene kicks up a middle finger to the charade.

The burgundy waistcoat is the only splash of real color in the film, and it’s no surprise only “Eugene” can indulge in it. What I love most is his hastily pulled tie; it can be taken as the work of a sloppy drunk, but for someone who is otherwise sharply dressed, it only personifies Eugene’s reckless abandon, which is the makings of true style; while Vincent hides in the guise of Jerome’s “just-like-everyone else” outfit of sober precision, Eugene kicks up a middle finger to the charade.

And this is what Gattaca does so beautifully. The clothes always exude personality and the journey of becoming. Early in the film, Vincent meets German, the man who would help him to become Jerome. A single shot pairs Hawke (in a mousy face and jacket he’ll never grow into) with Tony Shaloub (who’s character gave his tailor precise, curt orders). Young Vincent has his work cut out for him, and his transformation to board the ship to Titan (which astronauts board in suit & tie) was a feat his heart wasn’t supposed to handle. Much respect, Vincent.

And this is what Gattaca does so beautifully. The clothes always exude personality and the journey of becoming. Early in the film, Vincent meets German, the man who would help him to become Jerome. A single shot pairs Hawke (in a mousy face and jacket he’ll never grow into) with Tony Shaloub (who’s character gave his tailor precise, curt orders). Young Vincent has his work cut out for him, and his transformation to board the ship to Titan (which astronauts board in suit & tie) was a feat his heart wasn’t supposed to handle. Much respect, Vincent.

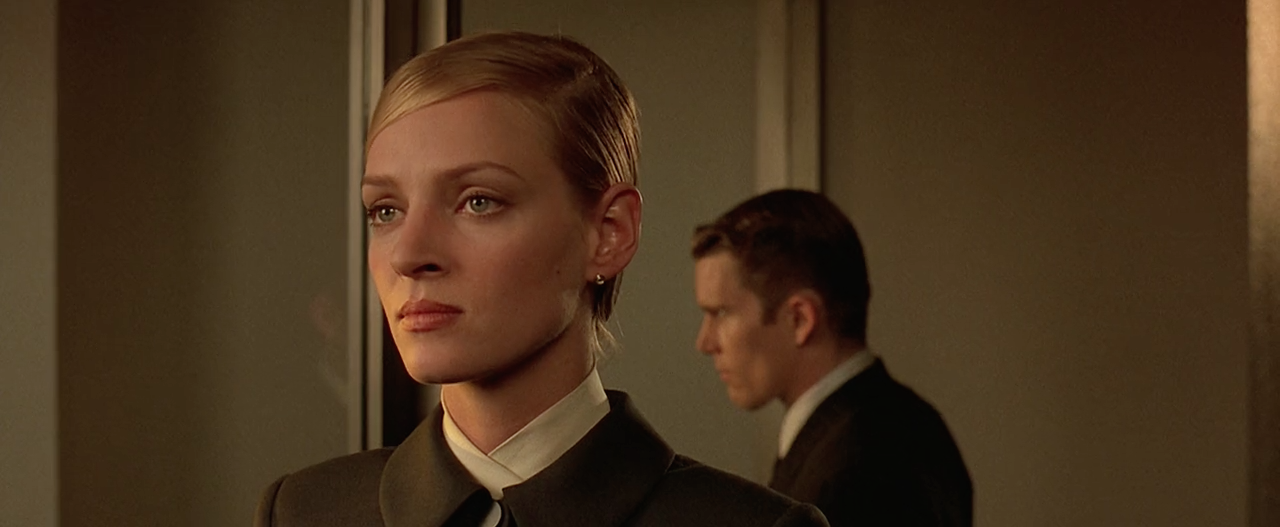

Now, as much as Andrew Niccol and his team created a visual masterpiece of timelessness in the film, they still had to deal with the future. Even so, they kept simplicity in mind, with appealing results. On fancier evenings, Vincent ditched the necktie and opted for a silk top-button cover that I think would kill; similarly, Irene’s work uniform topped off with an excellently layered “kimono collar.” Both great examples, none more beautiful than the smart watch.

Now, as much as Andrew Niccol and his team created a visual masterpiece of timelessness in the film, they still had to deal with the future. Even so, they kept simplicity in mind, with appealing results. On fancier evenings, Vincent ditched the necktie and opted for a silk top-button cover that I think would kill; similarly, Irene’s work uniform topped off with an excellently layered “kimono collar.” Both great examples, none more beautiful than the smart watch.

As much as I appreciate the recent advances of digital watches, I don’t think they’ll ever find a permanent place in a wardrobe. However, if it looked like the Gattaca watch, I’d be all for it. The brushed steel, small rectangular shape, black leather strap, and especially the absence of any visible tech form a subtle, wearable timepiece that can transcend eras.

As much as I appreciate the recent advances of digital watches, I don’t think they’ll ever find a permanent place in a wardrobe. However, if it looked like the Gattaca watch, I’d be all for it. The brushed steel, small rectangular shape, black leather strap, and especially the absence of any visible tech form a subtle, wearable timepiece that can transcend eras.

I could go on for days, but I’ll end with this: Gattaca is easily one of my favorite films. The original score evokes an emotion that pushes Vincent through his gauntlet. The moral quandaries of science is a discussion I can and have started in my classroom. Another lesson is in style: simple doesn’t always mean boring, and classic doesn’t always mean old. In a world of self-labeled sprezzatura hashtags and my own fastidious search for more daring patterns, this film is a great tribute to classic menswear. Aside from the chase for genetic flawlessness, I’d look forward to this kind of future.

Other Notes: