Is it a uniquely male crisis to fear being forgotten? Every stop of Derek Jeter’s farewell tour sizes up his contributions to the New York Yankees and his place in the club of men to throw on the pinstripes. As every POTUS before him, Mr. Obama is followed by debate of being remembered in history books as the “_______________” president. Hell, every damnable act Lord Tywin orders is for the sake of the Lannister name (well at least he says). So, if being forgotten is man’s fear, then how does man not become forgotten? An easy answer, I think, is to be something bigger than man.

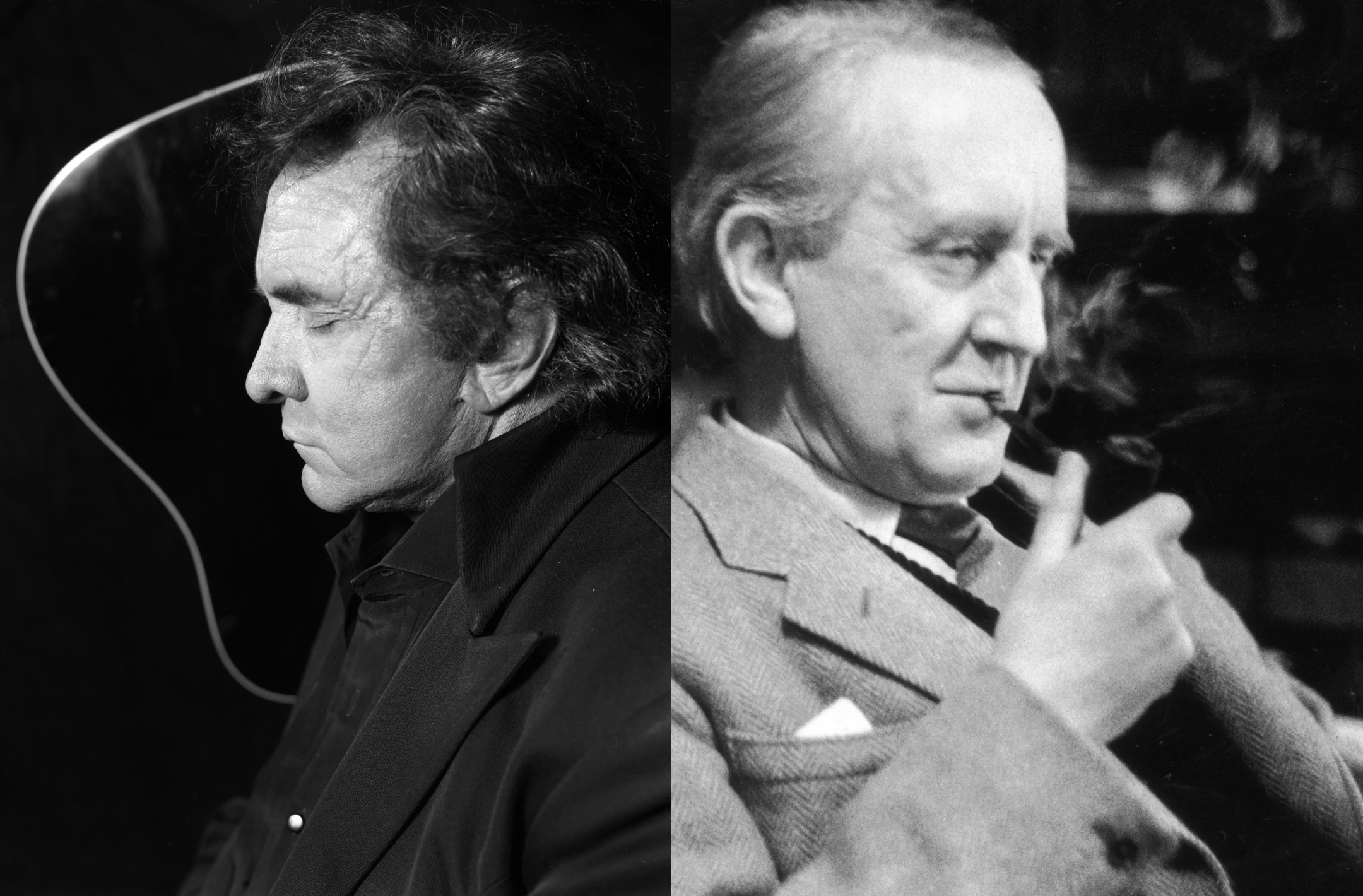

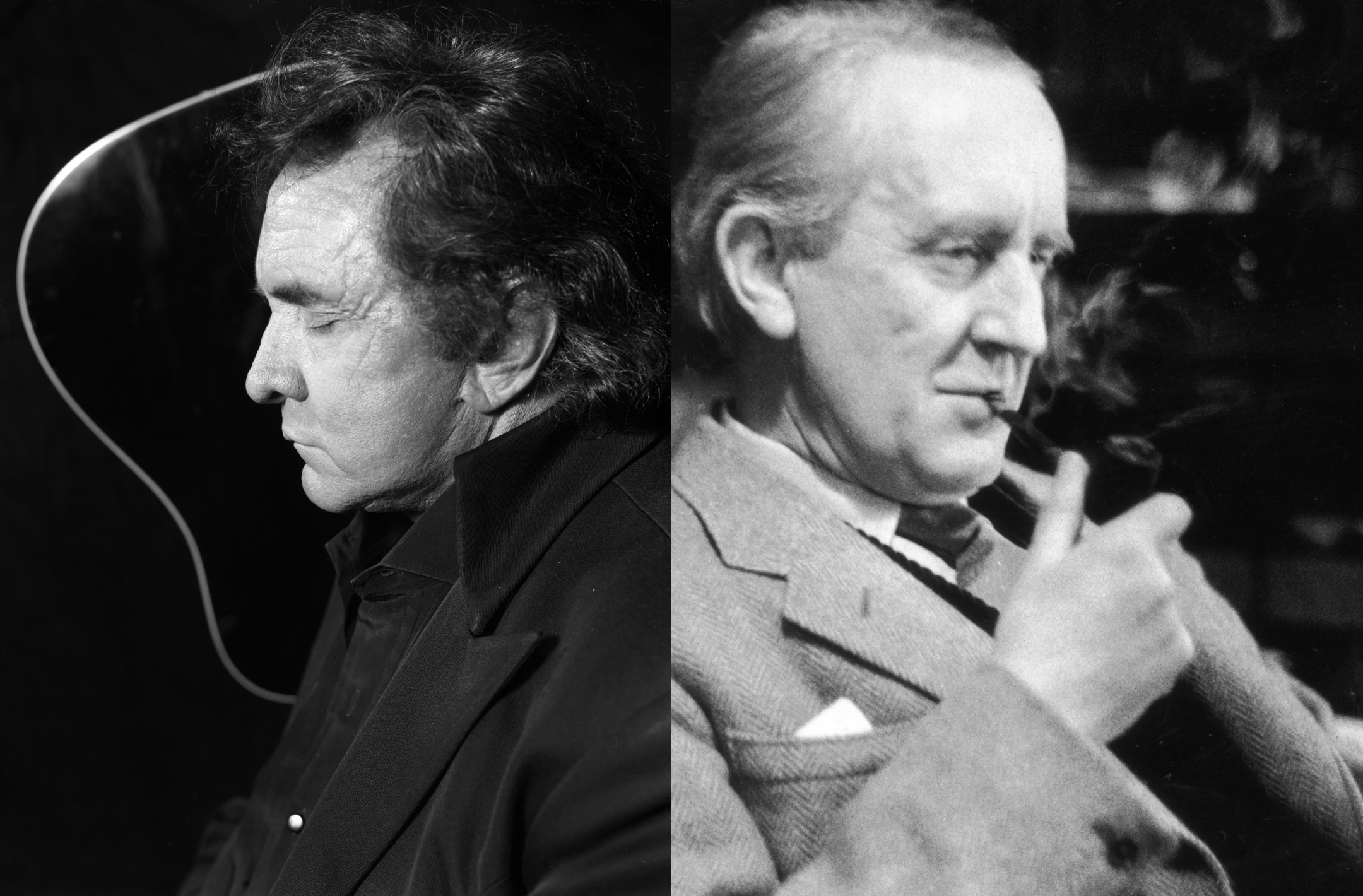

All boys want to become something like their heroes. Toughen up, grow lean, then face the world and all its problems with a shit-eating grin. As for myself? Well, watch me tiptoe down the corridor of my apartment to hurl a bag of trash into the bin while scurrying back to my door and call me tough. Nevertheless, I look up to idols who face the world and leave a worthwhile note about it. Men who flood the page with wit and honesty, who croon of life’s common pains and pleasures through an LP. This past month has seen the release of works from two such artists, JRR Tolkien’s translation of Beowulf, as well as the Johnny Cash’s Out Among the Stars. And what notes these are.

In literature, Beowulf – a classic epic poem about a Scandinavian warrior’s quest in defeating monsters, dragons and himself – is prerequisite in the gauntlet of texts one must annotate and analyze through a term paper before earning a bachelor’s degree in the subject. It’s also the first text that I utterly devoured on my own accord. The sheer epicness of the verse pounded like the protagonist’s battle-worn steel. And the names, my god, the names. Say out loud Beowulf’s sword – Hrunting – and from your lips you hear crushed bones and pierced flesh. At the moment, Seamus Heaney is credited to translating the Anglo-Saxon epic into the most articulate and powerful modern English form; I myself cracked the spine of my used copy in half throughout my study of the text. And Mr. Tolkien’s version will be released on May 22nd. Now, I must admit that I have not myself read Lord of the Rings or its companions, but since Tolkien’s reputation precedes him so, I await with geeky excitement. Why? Consider a sample:

Original Old English:

“. . . sund wið sande– secgas baéron on bearm nacan beorhte frætwe gúðsearo geatolíc”

Heaney’s translation:

“. . . warriors loaded a cargo of weapons, shining war-gear in the vessel’s hold, then heaved out,”

Tolkien’s:

“. . .Gleaming harness they hove to the bosom of the bark, armour with cunning forged then cast her forth to voyage triumphant,”

As any translated text, the story can only be as good as the person who interprets it. I adore Heaney’s version, but Tolkien’s appears to be an entirely new story together. And come on, it’s the author of perhaps the most revered fantasy saga in literature. Like I said, I can’t freakin’ wait to get my hands on a copy.

With healthy assumption, my generation knows Johnny Cash best, and maybe only, by his American Recordings volumes. Personally, I like to know him this way. For instance, I realized I never shared any of Mr. Cash’s music to my wife when I asked her opinion of “She Use to Love Me A Lot.” After a moment, Laura asked “Why is it so heavy?” Thinking she was talking about the recording quality, I asked and she answered by explaining that what she heard was something like singing, but more a man narrating about his life.

In one sentence my wife summed up why Johnny Cash’s music resonated in me. Take, for instance, “Give My Love to Rose.” When listening to his original recording, I miss the tired, barely-there singing voice of his American IV version. In the latter, there’s a wisdom and regret in the lyrics that anchor them with reality. This is the Man in Black to me. And this is exactly what you hear in Out Among the Stars.

I’m talking about Scandinavian kings and country balladeers like they belong in the same room because at this moment they do. Tolkien and Cash, legends of their craft, have left this earth for greener pastures, and both Beowulf and Out Among the Stars could have been completely passed on without an eye to read or ear to listen. In Tolkien’s case, he never intended his translation for publication, as it was a scholarly labor of love that was only accidentally discovered in the Oxford University Library. For Cash, this album was shelved after his record label saw his star all but faded with rough album sales and relapse, only to be found in a vault of other recordings just last year. So there you have it; after a bit of luck and good rat packing, we can now access two master works. All the while, I’m terrified of my own legacy, or rather the absence of it.

We as humans are here to tell our story and share it with others. That’s well and good, but what if no one listens? You know, we can’t all pen Middle Earth or sing Folsom prison. What if for the time that a man tells his story, he is forgotten the moment the story ends? The existential psychiatrist Irvin D Yalom said it hauntingly: “Some day soon, perhaps in forty years, there will be no one alive who has ever known me. That’s when I will be truly dead – when I exist in no one’s memory.”

Is there a silver lining here? Maybe. None other than Tolkien’s son, Chris, is serving as editor to his father’s work. Similarly, it was John himself who found his dad’s recordings. Just reading John’s Jr. reminisce elder Cash’s sessions breathes life back into a man no longer with us. We can’t be heroes to everyone, but if we give a damn, we’ll be heroes to somebody. And maybe that’s enough.