The face of a happy, happy boy.

Warehouse & Co. Type 1, lot 1000

Curated and Photographed by Simon, aka the Denim Whisperer

The face of a happy, happy boy.

Warehouse & Co. Type 1, lot 1000

Curated and Photographed by Simon, aka the Denim Whisperer

When you arrive at Sham Shui Po at 9pm, you catch a neighborhood in transition. The rattle of the night market clinks at the close of tarped storefronts. Overtime workers inhale kitchen steam and BBQ pork in corner dumpling houses. Engines run cold until sunrise.

On Ki Lung St., a lone urban runner takes advantage of unobstructed roadway. He may have settled on his evening pace, but it slows to a half-jog, eyes craning to a closed shopping kiosk washed in white light. At either side of this immaculately green box, a young man and woman hiss an outline of a graffiti piece that would be complete in three hours.

For as long as the owner of this kiosk is satisfied with the artwork, Amson and Ysoo of local collective Parents Parents have added another exhibition to Hong Kong’s expanding street art gallery.

As for the jogger, or passing driver, or other curious local stopping by: what do they think?

“There’s always someone who asks us what we’re doing,” recalls Amson. “In such a public space as this, some people will come down the stairs and say ‘I don’t like this art, why do you destroy the walls?”

For Amson and Ysoo, nights like this, spaces like this, and moments like these aren’t confrontations, but opportunities to give locals an understanding that street art isn’t destruction, but expression. Tonight is a preview for Parents Parents’ offerings at this year’s installment of HKwalls, a weeklong urban campaign to spread the local art scene one district at a time.

Chris Tuazon: What do you prefer: illegal work, or commissioned pieces like this?

Amson: Although this isn’t really like the original graffiti style — bombing and letters — I enjoy these projects. We’re allowed a safe pace, so we have the time for preparation, sketching, and coloring. That way, we can make it correctly.

CT: How did you get into street art?

A: When I was in grade school, I was really into this band called LMF. I really liked the style of their album cover, and I figured I could try to create something like it. LMF was the first hip-hop band in Hong Kong, and it introduced me to hip-hop culture, and at that moment I chose that graffiti would be a part of . . . I don’t know whether to call it a career or hobby.

CT: What is Parent’s Parents’ particular style?

A: Since there’s four of us in this group, we work together using the best of our different styles. For example, I like to draw my cartoon characters. Ysoo likes more realistic drawings, and freehand writing. So we combine these together to make something interesting.

CT: In this piece, “Time to Wake,” what are you trying to convey?

A: Since graffiti has a language, those who don’t know it can have trouble understanding and accepting what they see. So in this piece, the ticking clock, the morning apple, the strong contrast, and the title is all about what everyone’s typical day is like here.

CT: If someone saw you doing this and said “Hey, how can I do this?” What would you do?

A: I would let him know what the real culture is, and if he really wants to try it, I’d let him grab a can and go for it.

CT: So in other words, support the art.

A: HKwalls is really supportive of our local artists, and will bring guys from Europe to share their style and communicate with us. We’ve met crews from Germany, and we’ve learned from them, and not just their art.

These guys are street artists full-time. People in HK, like my family will say “If you do street art, you can’t get money. You can’t get a house. You can’t get anywhere.” But these guys prove if you really want to do what you want, one day you can succeed, and show your passion worldwide. For me, now I think about not just doing art within the HK scene, but out there.

CT: In the meantime, it seems that you feel pretty optimistic about the scene here.

A: It’s going up, because in the global culture more people are focused on the street art scene. Galleries out in LA and New York showcase it more than ever before. Maybe that will make the HK people welcome us and give the public more opportunity to really see the scene for what it is. Maybe there’s kids here who only illustrate on paper, and don’t realize what they’re doing. But at that moment they’re making street art. They’re creating real art.

“Time to Wake” can be found completed here. This year, HKwalls has chose Sham Shui Po as the local area to bring street art from HK-based and international artists, who will use new & old spaces as public canvas. Parents Parents are one of many to showcase their talents this March-April 2016. Follow HKwalls for more information.

I started this article the same way I always do: staring into a blank wordpress draft, ghost-tapping the keyboard, hoping a writer’s muscle-memory would find a way to begin. Then I’ll delete, and start the process again.

Writing’s tough, man. Expecting my students to compose a compare and contrast essay never ceases to hit me back with a pang of guilt. So as long as I assign writing, I’ll ask the same of myself.

But somewhere in the fifteen to ninety minutes in the trenches of writer’s block, I emerge with something worthwhile to share, and inspiration takes hold. It is at this moment that I am full with what I made this site for: purpose.

2015 was the first complete year of the honor roll. I’ve had the pleasure to meet and talk with unique artists, and the opportunity to contribute to their work, which I fully believe in. And from the artists, their work, and the people who value them, I have learned. And for that I am most grateful.

From this year I’ve selected twelve moments. If you’re a frequent reader of the honor roll, please revisit these pieces. If you’re new, I hope these stories will help you to understand why I love what I do.

Click on the photos to read the articles. Enjoy. Happy new year.

Every year, thousands of Hong Kong residents, young and young at heart, take to the West Kowloon Cultural District for another glorious Clockenflap Festival. The warm November air and bright city skyline stew together a weekend of celebrating music, art, and people. The best of Hong Kong shines for seventy-two hours of light and sound, and I wonder: what now?

It took me three years, but last winter came to an understanding: for all the gargantuan acts that attract the masses to this part of the city, something else entirely keeps us there: community. Now, as a visitor – frequent that may be – I’m curious to see what Clockenflap actually does for the city of Hong Kong. Does the magic of the Harbour Flap Stage flicker out with the Sunday headliner, or does it linger just long enough to inspire real action?

In between the main stage and the rest of the festival grounds, Clockenflappers must cross a grated steel footbridge. Back turned to the Central skyline, as you descend the end of the bridge four shipping containers are stacked two by two ahead. Upon this makeshift canvas lay the outlines of a large mural, currently indeterminable. Aerosol cans hiss and spurt morse code against a rumbling loudspeaker. Colors and lines take shape.

In a black and white letterman jacket, Stan Wu, co-founder of HKwalls, watches on, snapping pictures and explaining the work in progress to passers by.

Christopher Tuazon: What is HKwalls?

Stan Wu: HKwalls is an annual event in which we choose a district in Hong Kong, and we ask local and foreign artists to paint over public spaces within a weekend or two. In between that main event, we do smaller ones like this. These guys, Low Bros, came from Germany, and we flew them here this weekend to share some fresh ideas with the audience.

We want to bring more art that we love — street art, graffiti, exterior, urban, whatever you want to call it — to Hong Kong, because it’s dead right now.

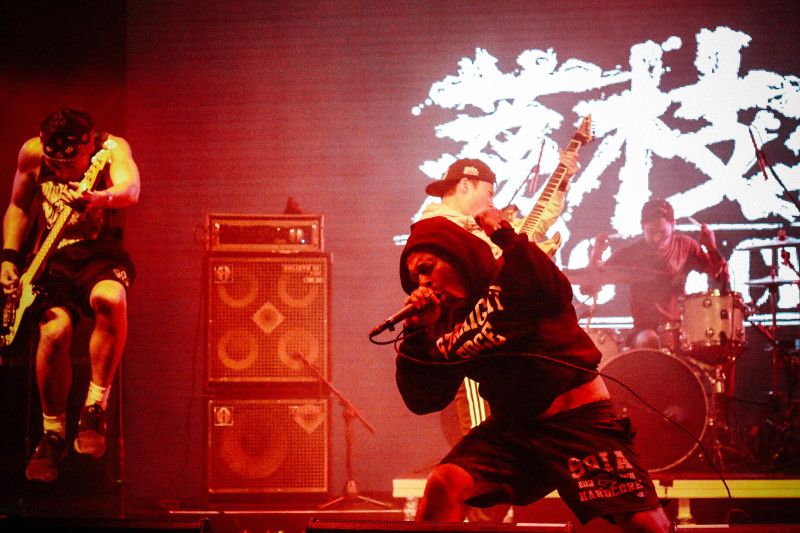

Adolescence in California lends a steady diet of local music to ignite a fire inside the youth. From the first NOFX Oy! Oy! to last TERROR two-step, punk and hardcore music armed kids like me with something to make us feel alive. For many of us in the West Coast, this music is at the very least is the soundtrack to our angst, and at-times the crucible that forged an identity.

To watch a punk rock scene, then, is to take an honest look at what the local kids are fighting for and against, and what language it speaks.

So what’s the Hong Kong flavor of this genre? If you’re going to ask anyone here, it’s King Ly Chee, a band who, sixteen years strong, has undoubtedly formed what anyone could recognize as the HK hardcore scene.

With his new ep, 生活的小偷, singer-songwriter Jing Wong offers a take on classic Cantopop, imbued with his jazz and Britpop upbringing. These parts create a whole message for his Hong Kong. On a surprisingly warm November noon behind the Clockenflap main stage, Jing lays out inspirations from and aspirations for a city he doesn’t wish to see leave so soon.

Christopher Tuazon: On any given Jing Wong tune, you play around with different genres. What’s your musical foundation?

Jing Wong: When I went to university in London, my friends and I would mostly play a lot of Beatles covers. That’s one of the reasons why I wanted to go to there. I love Britpop. Radiohead, Blur, Suede. Plus, when you’re in art school, you get to listen to a lot of weird shit, like Sun Ra.

CT: Pop and jazz definitely come through in your music.

JW: On my own, I’m more of a folk player. But I love laying jazz riffs with the guys on saxophone and harmonica. The connection is irreplaceable. Without words, we know where we’re going, and we go there together. It’s amazing. That’s what’s beautiful about Clockenflap, too.

I, like many others in the Asian region, owe a lot of my self-discovery in the world of style to The Armoury. It’s difficult to place a finger at what exactly this store does that holds such an influence, and it’s just as difficult to think where I’d be without their guidance. In a city of fast and fused garments, the aptly-titled retailer uses a few hundred square meters of territory, holding strong in the battle for good clothing.

Now in their fifth year, The Armoury’s sphere of influence has expanded into New York, instantly becoming a hit to an America that is poised for a return to form – at least, so I hope. In the meantime, we toast to friendships, success, and not spilling too much on a good suit.

Below is a birthday greeting I posted to my larger-than-life big brother, Luiz. I never told this story before today, and I get a good chuckle out of this one of many moments I tried to be like him. And for all you little siblings out there: that’s totally ok.

When I was a freshman in high school, I tried to run for class treasurer. I had no desire or knowledge of handling money, but my big brother had the position with his alma mater.

I was severely uncool in my first few weeks, but I had to present a campaign speech to the class of 2003 anyway. My big brother offered his speech totem: an orange hazard vest with the motto C.R.E.A.M. taped on the back. I didn’t know what whipped dairy had to do with managing accounts, but he helped me plan a speech and rehearse.

Came speech day, I grabbed the mic from my opponent, and I said the words “CASH RULES EVERYTHING AROUND ME,” in the most suburban of inflections.

And the class of 2003 went wild.

I used to get a lot of shit for trying to copy my big brother, but first of all, IT’S LUIZ; everyone wants to be him. But most of all, because everybody has a hero.

Last Saturday marked the fifteenth anniversary of Hong Kong’s premier denim outfitter, Take5. In between diminishing rations at the open bar, I wasn’t able to capture much. Nevertheless, the evening did teach me Benny Seki’s impact on the Asian denim scene.

Last Saturday marked the fifteenth anniversary of Hong Kong’s premier denim outfitter, Take5. In between diminishing rations at the open bar, I wasn’t able to capture much. Nevertheless, the evening did teach me Benny Seki’s impact on the Asian denim scene.

Where Uniqlo undershirts and high-twists are a godsend for my suiting options, I’ve yet to crack the code on surviving May-September in jeans. But this is a denim party, dammit!